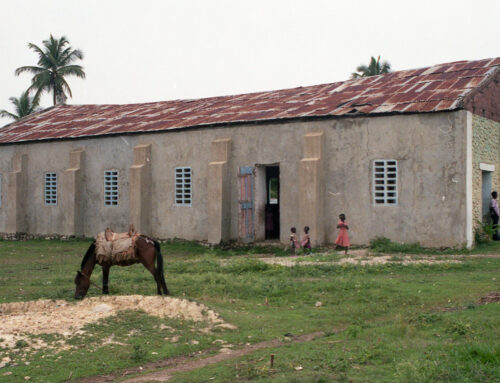

Last week, we mentioned François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, who ruled Haiti from the late 1950s to early 1970s (you can read the post here). Many of you are familiar with Papa Doc’s regime, but you may not know just how strongly he relied on Vodou. Duvalier’s time in power was marked by brutal political repression and strategic cultural and religious rhetoric that placed Vodou front and center. Vodou became so much a part of Duvalier’s public persona that he declared himself one with the loa (the spirits of Vodou) and an embodiment of “the Haitian flag.”1

For context, Vodou is a syncretic religion that combines elements of African traditions and Catholicism, dealing heavily in superstition, occult rituals, and appeasement of supernatural spirits. Duvalier, a physician by training, was acutely aware of the influence Vodou held over the Haitian people.2 In Haiti, Vodou is more than a religion; it is a cultural cornerstone, deeply intertwined with daily life and national identity.

Duvalier exploited this by positioning himself as a powerful Vodou figure. He adopted the persona of Baron Samedi, loa of death and the afterlife, and became known for his black hat, dark glasses, and cane, speaking in the nasal tones associated with zombies.3 By aligning himself with such an ominous spirit, Duvalier created an aura of invincibility and supernatural authority around his leadership.

This self-styled identification with the loa of death was more than mere symbolism. It had practical implications, as many Haitians came to believe Duvalier possessed supernatural powers. Duvalier reinforced this belief through various means, such as staging elaborate Vodou ceremonies, reportedly practicing dark magic, and spreading rumors of his mystical power.4 The fear of his supposed ability to summon spirits or inflict curses created a psychological barrier against opposition, making it easier for Duvalier to maintain control over the country.

Duvalier’s manipulation of Vodou extended beyond personal image-making. He strategically integrated Vodou into the state apparatus, particularly in his establishment of the Tonton Macoute, a paramilitary force that became synonymous with terror and oppression in Haiti. The Tonton Macoute, officially known as the Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale, was composed of loyalists who were often linked to Vodou practices.5

Papa Doc did not come to power in a vacuum. His use of Vodou found resonance because in Haiti, Vodou and politics were already linked—all his rule accomplished was to cement the relationship even further.

As we serve in Haiti today, we are mindful of this political context. The fear of Vodou still has a hold in many people’s lives—even believers—and this knowledge gives precision and urgency to our own gospel ministry. Only the hope of Jesus can break the power of fear in Haiti.

Visit Vodou in Haiti to read more about the religion and its history.

[1] Ndiva Kofele-Kale, “The Cult of State Sovereignty,” in The International Law of Responsibility for Economic Crimes, 2nd ed. (Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), 261.

[2] Elizabeth Abbott, Haiti: A Shattered Nation, (2011); rev. and updated from Haiti: The Duvaliers and Their Legacy (New York: The Overlook Press, 1988).

[3] Ulysses Paulino Albuquerque, et al. “Natural Products from Ethnodirected Studies: Revisiting the Ethnobiology of the Zombie Poison,” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2012), doi:10.1155/2012/202508.

[4] Albin Krebs, “Papa Doc, a Ruthless Dictator, Kept the Haitians in Illiteracy and Dire Poverty,” New York Times, April 23, 1971, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/04/23/archives/papa-doc-a-ruthless-dictator-kept-the-haitians-in-illiteracy-and.html; Dan Williams, “After Duvalier: Haiti: A Scary Time for Voodoo,” Los Angeles Times, March 7, 1986,

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-03-07-mn-16184-story.html.

[5] “The Tonton Macoutes: The Central Nervous System of Haiti’s Reign of Terror,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, March 11, 2010, https://coha.org/tonton-macoutes/.

Share This Story!

Join Our Email List!

Get our blogs delivered directly in your email, don’t miss an opportunity to read about our mission to save children and bringing the Gospel to Haiti.