In last week’s blog post, we briefly discussed the Tonton Macoute—the paramilitary and secret police force created by François “Papa Doc” Duvalier to execute his political agenda. Today, we’re looking at how the Tonton Macoute influenced the relationship between Vodou and politics in Haiti.

The name “Tonton Macoute” refers to a Haitian mythological figure: a bogeyman said to kidnap and eat misbehaving children.1 It was first associated with Duvalier’s enforcers when people began to disappear or be killed, seemingly out of thin air. The name alone evoked fear, but reports and rumors of the Tonton Macoute engaging in dark Vodou practices, such as curses and hexes, amplified their frightening reputation.2 They were perceived as having the ability to invoke supernatural punishment against anyone who opposed them. This belief in their mystical capabilities dissuaded resistance and fostered an atmosphere of dread amongst Haitian citizens.

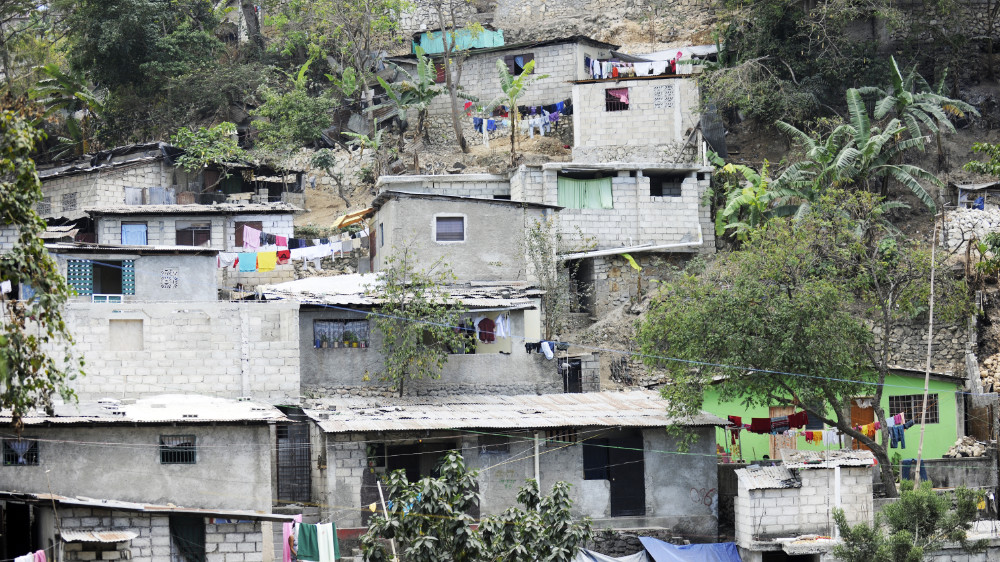

Tonton Macoute soldiers wore distinctive blue denim uniforms, dark glasses, and straw hats, and were armed with machetes and guns, making them a visible and intimidating presence throughout Haiti.3 Members of the Tonton Macoute also frequently came from lower socio-economic backgrounds, where Vodou was widely practiced and respected.4 By recruiting individuals familiar with and devoted to Vodou, Duvalier ensured that the Tonton Macoute were not just enforcers of his will, but also agents of cultural continuity. They worked within existing religious and cultural norms to instill fear among the people. The intersection of political power and religious belief played a critical role in their operations, making Vodou an essential tool in the Duvalier arsenal of terror.5

Members of the Tonton Macoute frequently participated in rituals to invoke the protection and power of the loa (spirits of Vodou). The belief that the Tonton Macoute had the backing of powerful spirits made them seem untouchable and their violence inescapable. The association with Vodou also contributed to their image as more than just a paramilitary force—they were seen as agents of a mystical, malevolent power that transcended ordinary human authority.6

Duvalier’s exploitation of Vodou included using fear of the supernatural to enforce obedience and discourage dissent. Because of this, Papa Doc’s reign over Haiti was marked by a calculated and effective use of Vodou as a tool of political control. By associating himself with powerful Vodou spirits and embedding Vodou practices within the Tonton Macoute, Duvalier created an atmosphere of fear and abject reverence that helped to sustain his brutal regime. This blend of political and religious manipulation ensured his dominance and left a lasting impact on Haitian society and governance.

Thankfully, the story doesn’t end there. God is kind, and He invites us to worship Him in confidence, not fear—through Jesus, we not only know the love of God, but we can experience true peace in Him. That is the message we share with the people of Haiti. In spite of the darkness, there is hope through the power of the gospel.

Visit Vodou in Haiti to read more about the religion and its history.

[1] Jeb Sprague, “A History of Political Violence against the Poor § The Blood-Soaked Record of the Duvaliers,” in Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in Haiti (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012), 33.

[2] “The Tonton Macoutes: The Central Nervous System of Haiti’s Reign of Terror,” Council on Hemispheric Affairs, March 11, 2010, https://coha.org/tonton-macoutes/.

[3] Bettina E. Schmidt, “Anthropological Reflections on Religion and Violence,” in Andrew R. Murphy, ed., The Blackwell Companion to Religion and Violence, Blackwell Companions to Religion, vol. 42 (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 121.

[4] Marvin Chochotte, “The History of Peasants, Tonton Makouts, and the Rise and Fall of the Duvalier Dictatorship in Haiti,” PhD diss. (University of Michigan, 2017).

[5] Paul Christopher Johnson, “Secretism and the Apotheosis of Duvalier,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 74, no. 2 (June 2006): 420–45.

[6] Bernard Diederich, Papa Doc & the Tontons Macoutes (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2009).

Share This Story!

Join Our Email List!

Get our blogs delivered directly in your email, don’t miss an opportunity to read about our mission to save children and bringing the Gospel to Haiti.